Swarovski, a Legacy of Beauty

By Sandy Nesoff Photos courtesy of Swarovski AG

Gold and diamonds have been the currency of the wealthy since time immemorial. No costume jewelry and no iron pyrites (fool’s gold). Is there anything more beautiful than a diamond necklace or ring or a bracelet of gold?

Absolutely.

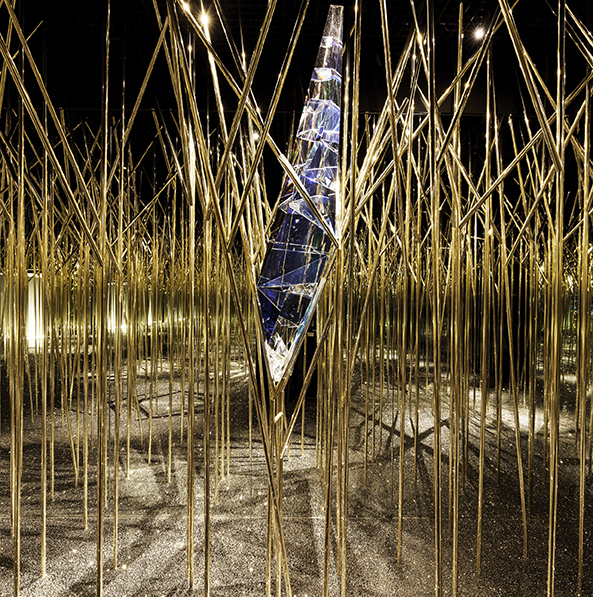

In the small Austrian village of Wattens, not far from the German border the face of a giant with an open mouth, water pouring forth, sits, waiting to greet visitors. It’s a strange and garish entry to what could arguably be one of the most beautiful collections in the world, Kristallwelten.

This is the Swarovski Museum holding the display of the most amazing man-made crystals ever created. They shine, they sparkle and many people can not tell the difference between a Swarovski crystal and the purest white diamond from the mines of South Africa.

In the entrance, enclosed in a giant glass case, is a huge crystal in the shape of a diamond waiting to be set in en engagement ring for a women of ginormous proportions. But that is only the start. Just a short distance further into the museum is the life-sized effigy of a horse bedecked in a saddle, bridle and stirrups with thousands of crystals adorning them.

It was custom made for an oil rich Arabian sheik who, no doubt, rides it through the sand dunes of his native “wherever.” His identity and nationality are not disclosed.

This is only scratching the surface of the man-made crystal artifacts throughout the museum. There is room after room, each one more amazing than the one before it. Most of these crystals were made for display in the museum rather than for purchase by the amazingly rich. Even “The” Donald Trump would have difficulty scraping his wallet to bring home some of the crystals.

And don’t even think of requesting a visit to the facility where they are created. That comes under the heading of “If I tell you, I’d have to kill you.”

Well, OK, not really. But the Swarovski facility where they are given birth is strictly off limits to any but the trusted workers who ply their trade there. The process has been a closely guarded secret since Daniel Swarovski first brought them into the world.

Swarovski, who was born in 1862 and passed away in 1956, was born in Northern Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) as Daniel Swartz. His father was a glass cutter and the young man served an apprenticeship at his father’s side. There he learned the fine art of precision glass cutting and in 1892 he patented an electric cutting machine to facilitate the production of crystal glass.

Three years later he partnered with financier Arman Kosman and Franz Weiss, founding the Swarovski Company. Originally known as A. Kosman, Daniel Swartz & Co., it was shortened to K.S. & Co.

They set up a factory in the Tyrolean village of Wattens to take advantage of the inexpensive hydroelectricity needed for the grinding of their process. It was energy intensive and the least expensive method was to set up near strongly flowing water.

Today the secret process turns out finely cut crystal glass sculptures, miniatures, jewelry, couture, home décor and magnificent chandeliers.

It is known that to create glass tat permits light to refract in a rainbow spectrum, Swarovski coats some of the products with a special metallic chemical coating. One such method, Aurora Borealis gives the surface a rainbow appearance. Swarovski brands each of its products with a swan to authenticate it.

Over the years Swarovski has expanded beyond crystal jewelry and the like to produce abrasives and optical instruments such as binoculars and rifle scopes. They have also created a range of fragrances, including both liquid and solid perfumes.

Ever on the move, Swarovski partnered with electronics giant, Phillips, to produce crystals for the electronic field such as USB memory chips. They now also include Bluetooth wireless earpieces.

But for all the expansion the company is still best known for its jewelry and figurines. Many shopping centers around the world are now home to Swarovski stores and there are shops in many airports.

Swarovski crystals were embedded in collectible silver coins issued by the Canadian mint in 2009.

The whole world is familiar with the annual lighting of the Christmas tree in Rockefeller Center. Sitting atop the giant tree since 2004 is a crystal star in the shape of a snowflake made by, of course, Swarovski. Smaller replicas of the star are sold as annual edition ornaments for home tree use. The one that sits atop the tree is nine feet in diameter and weighs in at 550 pounds.

Swarovski made it into the movies in the 2004 film version of Phantom of the Opera. The standing model of the chandelier was composed of Swarovski crystals and in one scene a Swarovski shop window is visible.

And again in 2009 the documentary film “This is It,” starring Michael Jackson, the entertainer wore costumes covered with Swarovski crystals.

Pop singer J-Lo had Swarovski product-placed for the single “On the Floor” along with such noted brands as Crown Royal rye and BMW automobiles. It appeared again in the Nelly Furtado Big Hoops music video.

There’s little reason to shop around for a better price when buying Swarovski. The product is tightly controlled to avoid having it sell off at bargain prices. What you might buy in Munich will sell for about the same cost in New York.

Some of the more popular pieces are a miniature crystal typewriter with a piece of paper as though a newsman were in the process of preparing an article; a tic-tac-toe set with the pieces made of crystal, lady bugs, flowers, animals and fine jewelry.

Even though the pieces might be on display in such locations as a hotel in Innsbruck, Austria, they are only for display purposes. A visitor to a hotel there asked to purchase a necklace of Swarovski crystals. He was told he had to go to the Swarovski store in the city’s Old Town. Amazingly, the available collection in that store was far wider than at the Swarovski museum store. But the prices were the same.