My New York Story

By Lee Gabay

It’s Ten 0’Clock

Twenty years ago, when I began teaching middle school in the Bronx, my day always ended with the Ten 0’Clock news. While I scurried around my East Village apartment preparing the next day’s lessons, grading papers and making tomorrow’s lunch, the Ten O’Clock news was my soundtrack. Periodically, I would stop in front of the TV to watch the weather to know what clothes to wear the following day or tune in to see the usually disappointing Knicks highlights. In more than the literal sense, local TV journalists Rosanna Scotto, John Discepolo, Cynthia Santana and a host of others became my anchors. These real-life, on-air personalities taught me how to skillfully communicate and navigate the many challenging people and situations that are thrust upon a first year New York City teacher.

Newscasters have strong voices and speak with authority. Yet they are always approachable. I am generally a confident person, but teaching, particularly teaching in New York City, can be humbling and I needed to adjust my classroom persona to adapt to the joys, resistance, successes and shunning I was to experience. Broadcasters never raise their voice. Even during the most difficult stories or interviews, they remain outwardly cool and in control. Borrowing from that, and rather than getting into a shouting match with twenty-five eighth graders, I looked for the few students who were on task and praised them copiously. Students feed off compliments more than they grow from criticism. Their unwelcome noise soon dissipated as the quality of their work elevated.

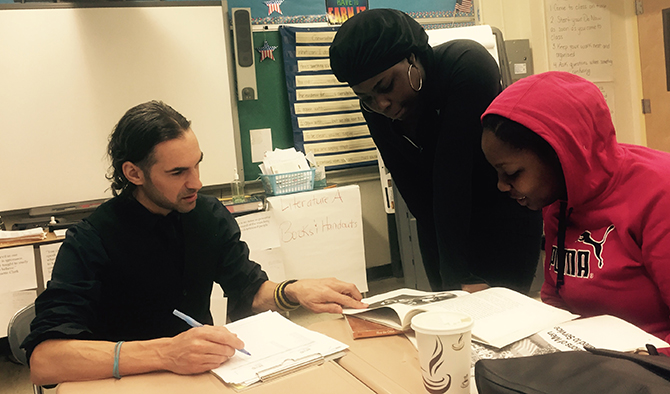

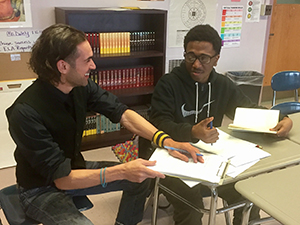

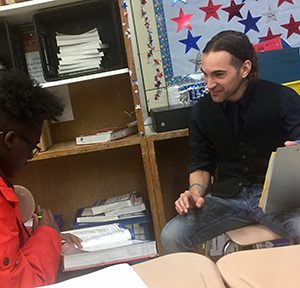

The most interested person in the room

I further studied broadcasters and saw that they all shared a genuine curiosity about people. The more the subject shined, the better the segment. Rather than being the focal point of the lesson and bloviate for fifty minutes, the class and the work were about the students. I needed to remind the students of their value and not my own. I became the most “interested” and not the most “interesting” person in the room. From watching newscasters, I honed my ability to ask good questions, to listen and to retain that information.

Recently, when local TV news journalist Linda Schmidt visited my classroom in Brownsville, Brooklyn to do a story on the impactful work being done at the school, she asked me why I teach. I answered, “Similar to you, I am interested in people.” We had a wonderful conversation, agreeing that our jobs provide us with a front row seat to all that is great about the city and, sadly, much of what is difficult.

Five years into my teaching career I switched schools to Passages Academy, a school for court-involved youth inside the city’s correctional facilities. Inside the Juvenile Detention Center, I had a student named Samantha who was a 14-year old misanthrope. She was moody, nasty, a poor speller and mistreated the entire staff. Her mouth was lethal. However, she was also occasionally very charming and a great dancer. Working with her reminded me of on-location field reporters, always wondering what unexpected circumstances may arise. I began to watch these on-air reporters — these “street magicians” — and marvel at the elegant way they handled themselves with difficult people and spontaneous situations. Though I would never claim to enjoy my moments with Samantha, she did deserve – and receive – my respect and engagement for simply allowing me the privilege to teach her.

Streetwise

New York is the biggest media market in the country. It also is home to the largest school system in America with over 75,000 teachers and 1 million students. Educators and the media cover a lot of pavement and use the city to our collective professional benefit. I currently teach at Brooklyn Democracy Academy, a transfer high school serving over-aged and under-credited students. Many have been through the juvenile justice and foster care systems. This is essentially a last chance high school. What separates these struggling students from successful students is access and opportunity to our city’s phenomenal resources. These habitually disengaged students didn’t care for school because, as many have told me, they felt as if school “didn’t care for them.” They viewed classrooms as unsafe spaces with people who were out to prove them wrong. Heeding the students’ words, I now spend my days thinking of new ways of educational engagement, and I use a reporter’s mindset by taking full advantage of our surroundings. The city has become an extension of our classroom, exposing the students to plays, sports, music, museums, galleries, culture, cuisine and so much more. Encompassing our various walks of life, what all New Yorkers seem to have in common is caring and contributing to the well being of our young people. Playwrights, politicians, authors, actors, activists, intellectuals, merchants, mechanics, athletes and designers have visited the school to spend time with the students and share their stories.

Affirmative Actions

Early on in my teaching career, after a lesson where the class read a newspaper about a murderer, a student named Marcus said to me, “Gabay, I get enough negativity at home. I like you and your class, but I like it best when you keep the lessons positive. Today’s article and discussion was fine, but it wouldn’t hurt you to find something happy.”

Marcus taught me that I failed to acknowledge the grace and positivity in their worlds, and in my attempt to connect with the students, I brought in magazine articles, songs and books that all shared a heightened sense of urban drama and sensationalized danger. I found myself playing into hackneyed imagery of violence and adversity as a means to capture their attention and win them over. In broadcast news terms, I was going for ratings vis-a-vis the “if it bleeds, it leads” mentality. Marcus helped me learn, counterintuitively, that the more inspiring a story is, the more powerful can be its impact. I soon noticed improvements in behavior during class and even a rise in the number of students completing homework assignments. It took an icon such as Ernie Anastos to reinforce this positive context shift. His daily “Positively Ernie” segments reiterated my student’s suggestion from years ago. When Ernie invited me to join him on air in studio, it was a testament to Marcus’s wisdom, which improved my professional effectiveness and has sustained my teaching career. Speaking with Ernie live on the Six O’Clock News as the subject of an uplifting news story validated Marcus’s powerful advice to me of praise and inspiration. Perhaps in my case, and certainly for Ernie Anastos, longevity comes from positivity. Teachers and TV news journalists provide a public service and, at best, we can create a body of work that is honest, authentic, and celebrates the human experience.

Lee Gabay is a doctor of Urban Education who teaches in Brooklyn, N.Y. He has written about education, incarceration, basketball and sneaker culture since 2006. His first book, I Hope I Don’t See You Tomorrow was published in 2016. He lives in the Lower East Side with his wife and daughter.