NYC & THE CIVIL WAR: IT’S COMPLICATED

By Ian Reifowitz

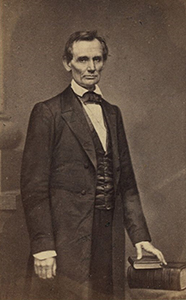

Abraham Lincoln

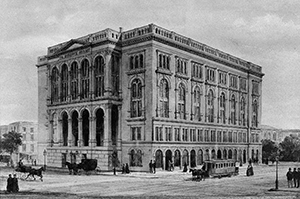

Abraham LincolnNew York City and the American Civil War have a more complex relationship than many New Yorkers may realize. On the one hand, our city is in the North and sent many thousands of young men to fight for the Union. Abraham Lincoln, then running for President, came to our town, where he delivered a speech on February 27, 1860, at the Cooper Union that, according to leading Lincoln historian Harold Holzer, made him president.

The city remembers that war at Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza, where we have the Soldiers’ And Sailors’ Arch—designated a city landmark 44 years ago—which is dedicated to “The Defenders of the Union, 1861-1865.” But those aren’t the only elements of the story. Take a look at the sentiments one New Yorker expressed regarding the question of whether the city should support the Union effort: “Why may not New York disrupt the bands which bind her to a venal and corrupt master—to a people and a party that have plundered her revenues, attempted to ruin her, take away the power of self-government, and destroyed the Confederacy of which she was the proud Empire City?”

SECEDE FROM THE UNION?

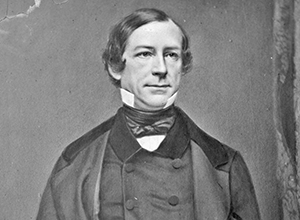

You might be thinking: that’s just one New Yorker, so what? The person who said that, however, wasn’t just anyone. He was Fernando Wood, New York’s three-term Mayor, who made these remarks to the City Council on January 6, 1861. Going further, he proposed that Manhattan, Long Island (as a geographic unit), and Staten Island should themselves secede from the United States and become the Free City of Tri-Insula. Mayor Wood argued that such a step would allow New York to “make common cause with the South.” Of the South, he also said: “With our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States, we have friendly relations and a common sympathy.”

The Draft Riots of 1863

The Draft Riots of 1863The Council gave its assent, briefly making secession the official policy of New York City, at least until after shots were fired at Fort Sumter that April and the war officially began. Nevertheless, according to historians, a significant percentage of New Yorkers sympathized to some degree with the Confederacy throughout the war. Slavery and the cotton trade were decisive factors in making New York rich, and many on Wall Street and in other related fields of manufacture and commerce simply didn’t want to give that up. According to John Strausbaugh, the author of City of Sedition: The History of New York City During the Civil War, “New York was arguably the most pro-South, pro-slavery city in the North because it had a very long and deep involvement in the international cotton trade.” Interestingly, the general assessment is that pro-Union sentiment was stronger in Brooklyn, then its own city and the home of the famed 14th Brooklyn Red Devils—the only Civil War regiment to bear the name of a city in its moniker.

Those who sympathized with the Confederacy were not limited to members of the economic elite. Many of New York City’s white laborers had little interest in seeing the end of slavery, which they believed would lead to ruinous competition over jobs between themselves and the newly liberated black population. Amazingly, a quarter of New York’s population on the eve of the Civil War was born in Ireland, and most worked as unskilled laborers. They were economically vulnerable, to say the least.

The Cooper Union

The Cooper UnionA SPARK IS SET

The fears and resentments of these white working-class New Yorkers remained in check during the war’s first two years. However, the Emancipation Proclamation—issued in late 1862 to take effect on the first day of 1863—raised the tension level as the promise of black laborers coming north loomed. What set the spark ablaze was the Civil War Military Draft Act, which became law on March 3, 1863. Only citizens could be drafted, and as most African Americans had not yet become citizens, the draft law affected few of them—although many black Americans volunteered and served heroically in any case. Nevertheless, anger at the draft focused on blacks, as well as on the wealthy who, according to the law, could escape service even if selected by paying $300 or hiring a substitute.

The first names of New York men to be drafted were selected on July 11, 1863. The city remained calm. When another set of names was drawn two days later, the city erupted. By the time order was restored on July 16th—which required the dispatch of federal troops—119 or 120 people had been killed. Rioters had lynched eleven African American men, and enough blacks fled New York City for Brooklyn that it altered the city’s demographics in a meaningful way for decades. The Draft Riots are likely more familiar than Fernando Wood, thanks to their depiction in the 2002 movie Gangs of New York.

As our country reels today from a white supremacist movement given fuel by the push to remove monuments of Confederate figures, New Yorkers are discovering that we’ve got Confederate monuments here too. After the white supremacist terror in Charlottesville, Virginia in August, Bronx Community College got rid of busts of Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Two Lee plaques in Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn have also been removed.

Mayor Fernando Wood

Mayor Fernando WoodI certainly don’t want to overstate the case here. Although New York City was not 100 percent on board with the Union cause, it was overall pro-Union. Fernando Wood was succeeded as Mayor by Republican George Opdyke, who ran and won in 1862 as a vociferous backer of Lincoln. A staunch, long-time abolitionist, Opdyke had previously been a member of the anti-slavery Free Soil party.

While it is impossible to tell the whole history of New York City during the Civil War in one short article, the point is that that history is not as one-sided as many of us might believe.

Ian Reifowitz is a professor of history at Empire State College of the State University of New York and a Contributing Editor at the political website Daily Kos. In 2014 he earned S.U.N.Y. Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Scholarship. His most recent book is Obama’s America: A Transformative Vision of Our National Identity.