Mart Crowley: After 50 Years He’s Still the Leader of the Band

By Ellis Nassour

In 1967, when Mart Crowley began writing his play The Boys in the Band, he was so frustrated with his career as a screenplay writer that he intended, with every breath of each invented character and situation, to be controversial. The themes of the play were self-loathing and self-destruction, the loneliness that envelops you when the crowd disperses. “These were things that fascinated me,” he revealed. “Things I was hung up on much too long. I tried to learn how people become their own worst enemies. Once I came to grips with that realization, I became a happier person.”

When the play opened Off-Broadway a year later, his intentions were well served. It became a sensation, and one of the longest-running Off Broadway shows (just short of 18 months; 1001 performances). It went on to thousands of regional and world-wide productions. An Associated Press blurb read: “One of the few plays that can honestly claim to have helped spark a social revolution.”

Soon after the praise for the blistering portrayal of his nine diverse characters, the play opened a powder keg of emotions just as America’s gay pride and identity movement opened another powder keg after the Stonewall Inn arrests. The onset of the fateful AIDS crisis came next. Gays fought for research funding and a better portrayal of themselves. Crowley’s play was considered divisive, too-stereotypical. He never imagined he and his play would be targeted and so reviled. The fame was not short-lived; however, the cheers were.

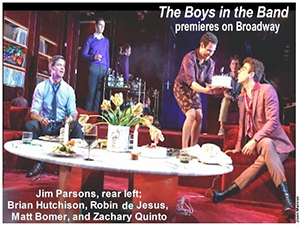

Now 50 years later, after the play has been revived three times, produced regionally and worldwide, andfilmed with its original cast, the playwright and The Boys in the Band are making their Broadway debut amid great fanfare. It is subdued compared to back when it became the first homosexual-themed play to reach mainstream audiences.

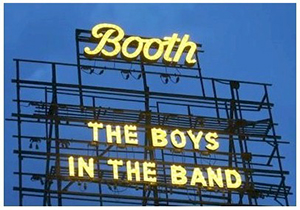

“I’m back!” laughs Crowley. “The band is still playing. Who in the world would ever believe this would happen? I’m extremely blessed for all the good fortune at this time in my life.” This was the day after he stood across the street from the Booth in pouring rain as the giant sign high atop the theatre blazed the play’s title in lights over the Theatre District and the theatre marquee with the play’s title and his name were lit.

Though you’d never guess, unless you do the numbers, Crowley turns 83 in August. Success and life may have had their ups and downs, but now transplanted back to New York after a storied life and career in Hollywood, he feels a spry 38.

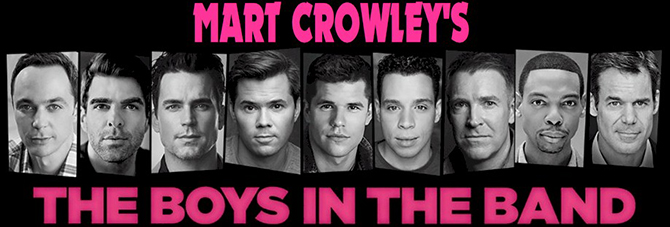

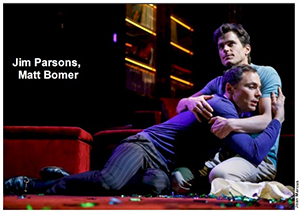

No less impressive than the play’s revival, co-produced by Scott Rudin and Ryan Murphy, is the cast of eight stage, TV, and film stars – and one newcomer, headlined by Golden Globe and four-time Emmy winner Jim Parsons, Zachary Quinto, Tony-nominee Andrew Rannells, two-time Tony nominee Robin de Jesús, and Golden Globe winner and Emmy nominee Matt Bomer. Two-time Tony-winner Joe Mantello directs.

Responding to the controversy his play stirred, Crowley says, “The Boys in the Band is no sermon. I’ve giving no one advice. What do I know about social causes? I had no hidden agenda. If anything, my agenda was very much other there. I was writing for personal fulfillment and for my own survival after years of frustration and failure. It all came onto the page, maybe even boiled over, rather quickly and easily.” He says there is “a little of me in some of the characters, and a lot of many people I have known, but the black comedy is not a confession, nor is it autobiographical” – although there’s some dialogue that draws personal parallels.

The Boys in the Band is set in an apartment in New York Upper East Side, as Michael (Parsons), a once successful film writer now between jobs, holds a birthday party for his bitingly-frank and sarcastic friend Harold. The guests include five gay friends, a hustler (Harold’s “present”), and Alan, Michael’s straight, married former college roommate, who arrives unexpectedly and in the throes of a personal crisis.

Though the play unleashes a fast stream of hilarious gay one-liners, it has moments of brutal honesty after Michael, drinking heavily, initiates a cruel truth or dare game where each guest must call the person he has loved the most. With the laughter faded and raw wounds opened, the birthday cake, strewn gift-paper, streamers, and confetti are the detritus of a disastrous event.

The success of the play came just in time for the Vicksburg, Mississippi native, who as a youth immersed himself in community theater and countless hours daydreaming at the movies. He went as far as making movies with his uncle’s camera in the city’s military park that traces the siege that Ulysses S. Grant inflicted on the city.

Hollywood was his dream and it appeared he was on the right and fast track. “But, and isn’t there always a but?” he says. “I was dried up in LaLaLand, and so exasperated at trying to make it as a screenwriter and being shut out that I considered throwing in the towel.” However, success at 32 was also tough. Crowley faced stress, depression, and alcoholism.

After his 1953 graduation from Catholic school, Crowley didn’t head to college – the Catholic college his father wanted for him, Notre Dame, but hopped a few buses to California, didn’t go to UCLA but got a job washing dishes in the cafeteria, and visited movie lots. His dream was to attend UCLA film school, “but dad said it was out of the question.” He’d read that Catholic University of America in Washington had an excellent drama department. “That led to a compromise.”

Home for Christmas in 1955, Crowley discovered through a family friend in Greenville that Elia Kazan was shooting Baby Doll, based on the Tennessee Williams’ rowdy short story set in the Mississippi Delta. Kazan and his stars Carroll Baker, Karl Malden, and Eli Wallach were eating in the friend’s Greenville restaurant. No one ever tore rubber on a highway faster.

“I knew Kazan’s work and was in awe of him,” said the playwright. “I went up and introduced myself and asked him a lot of questions. I was ready to quit school and go to work for him. He seemed amused, but advised, ‘Go back to school. Get your education, then come and see me.’”

Crowley went back to school, but it was UCLA, and to work on an art degree. He briefly became an illustrator, then returned to Catholic University, majoring in speech and drama and working in college productions and summer stock. “Those summers on the road was when I began to write.”

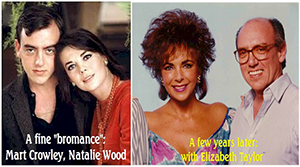

Back in New York after university, Crowley phoned a Baby Doll crew member. He got a job as a PA on the 1959 remake of the prison break film The Last Mile, starring Mickey Rooney. That led to jobs on another Williams adaptation, The Fugitive Kind starring Marlon Brando, Anna Magnani, and Joanne Woodward; Butterfield 8 with Elizabeth Taylor and Eddie Fisher; and others. Then, one night in New York, Crowley literally ran into Kazan walking. “The first thing he said was ‘What the hell took you so long’ I told him what I’d been doing, he told me to come see him, and I was hired as an assistant on Splendor in the Grass.” He impressed the director with his culinary expertise creating Greek salads and became Natalie Wood’s shoulder to cry on when it came to Warren Beatty. It was the beginning of a long, beautiful friendship.

Jump forward to 1960, Wood was starring in West Side Story and needed an assistant. “Lots of scripts and novels came in for her. Natalie trusted me enough to ask me to read them and tell her what I thought. Knowing how badly I wanted to write, she told me if I returned to California she’d introduce me to an agent.”

Recalling Wood, Crowley states, “Finding someone as precious as Natalie was so special, so rare. She was a warm, caring, wonderful, extraordinary person. We became awfully close.” The pressures of stardom and romance led to problems for Wood, twice leading her to attempt suicide with sleeping pills. Crowley discovered her the first time, unconscious, and rushed her to the hospital, where he registered her under a pseudonym. He became part of the family, helping husband Robert Wagner “over some rough spots, as well.”

Crowley was devastated by her drowning. He is godfather to Wood’s two daughters – one by second husband producer Richard Gregson; the other, her second marriage to Wagner. Wood stipulated that in the event of her death Crowley would be second in line after Lana, her older sister, to raise the children.

Wood came through. Crowley was signed by the giant William Morris agency, an unknown on a roster of megastars and Oscar-winning writers. He was hired as a contract writer. “It was very much like those scenes in Sunset Boulevard of the writer’s offices -- writing all day, with trips to the water cooler and roaming the back lot, but to no avail.”

There was a screenplay for Wood, optioned by Twentieth-Century Fox, which never made it past studio chief Darryl Zanuck [Crowley was to make a triumphal return to Fox years later]; and 1968’s Fade-In, to star Burt Reynolds. However the studio brought in another writer [it was never released theatrically, but occasionally pops up on TV retitled Iron Cowboy]. With the first money he made from Boys, he paid to have his name removed from the negative. “No one tried harder,” he points out, “but nothing ever panned out. Plays were rejected. Film scripts that were optioned never got off the ground. TV pilots I wrote never got picked up. It was one flop after another. I went from being an optimist to a pessimist.” He was also hurting financially. He’d housesit for stars, and at one point needed to sublet his apartment.

“On days when I didn’t have one martini too many, I’d fall asleep on the couch. I tried to get motivated by thinking up projects usually for me, not for the studio.” One idea came to him was while he was at a birthday party surrounded by very interesting people. I started mulling that over. The title came from a Judy Garland line in A Star is Born, but the stimulus that motivated Crowley was a piece in The New York Times about closeted drama. “I wondered why our leading playwrights didn’t really write what they were writing about instead of beating around the busy. I thought, ‘Why hasn’t anyone done that?’”

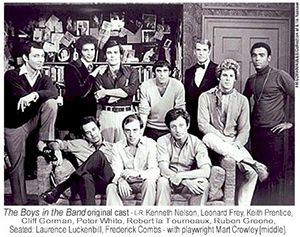

In July 1967, he got a call from Diana Lynn, a film/TV actress adept at comedy, drama, and the piano [she starred opposite Ronald Reagan in Bedtime for Bozo], who asked him to house-sit her Beverly Hills mansion. “For five weeks, I sat in the library and fought off the servants and wrote. It was there that I got the idea of setting the play at a birthday party.” He met with a New York agent. Her reaction: “A play about homosexuals at a birthday party! I can’t send that out. Come back in five years.” The comedy/drama was worshopped in 1968 at the Playwrights’ Unit in a small Greenwich Village Theatre [now, the Soho Playhouse] under the aegis of producer Richard Barr, instrumental in the career of Edward Albee. Word spread and soon there were lines around the block of those hoping for a ticket to one of five performances. When funding came up short, Crowley and the actors passed a hat around to the waiters at Joe Allen’s, where Allen made a sizable investment. “They all came out pretty well,” laughs Crowley.

The Boys in the Band premiered in the mid-50s way west of the theatre district and was an instant if controversial hit. It became a celebrity magnet drawing the likes of Jackie Kennedy, Marlene Dietrich, Rudolf Nureyev, and Groucho Marx.

New York Times critic Clive Barnes called it “one of the best-acted plays of the season” and “quite an achievement,” adding “I have a feeling that most of us will find it a gripping, if painful, experience – so uncompromising in its honesty that it becomes an affirmation of life.” Those were words Crowley never forgot and, in his darkest days, would repeat over and over. The play brought Crowley the prestige that had eluded him in Hollywood. The major studios wanted the rights “but didn’t want my involvement. I probably would have done the first draft of the screenplay and then lose control. I wanted it done right, with the cast of the play and with me as producer. No way! So, I settled for less money but got what I wanted – including a brilliant director, future Oscar winner William Friedkin.

The film did well, and has become a cult classic. Crowley suddenly had more money than he’d ever known: from royalties from Off Broadway, touring companies, regional, the West End production with the original cast, and worldwide productions, and income from the film. “It didn’t last forever,” he regrets, “particularly the way I lived.” In 1973, for six years, he “sort of evaporated” and tried to regain momentum in Paris, the south of France, and Rome. “You see where the money went, but like Edith Piaf, I am regret free.”

Wood and Wagner remained loyal friends. Crowley returned to the West Coast and 20th Century-Fox to be executive story editor and later producer of Wagner’s hit series Hart to Hart. Due to the intense stress, he left after four seasons – returning to write two TV movie specials. Not long after, he collapsed following a massive heart attack. “That was my wake-up call to stop drinking and change my diet.” Wagner, who attended the Transport Group’s 2010 Obie-winning revival, with audience members seated throughout the playing area, came in for the Broadway premiere.

Mart Crowley flung open a door 50 years ago and the closet hasn’t been shut since. There were other plays, including A Breeze from the Gulf, a brutal, thinly-disguised family life story in the mode of Eugene O’Neill and Albee. One critic wrote: “A deeply-religious alcoholic father, a dope fiend mother — well, what chance does an only son have for happiness?” It co-starred Ruth Ford, the beautiful model turned actress, who lived in the famed Dakota on Central Park West where she became muse to writers, actors, and musicians. It opened way Off Broadway, on New York Upper East Side. Reviews were strong to mixed, but it failed to find an audience. In retrospect, many feel it was ahead of its time and is ripe for revival.

The play can be found in 3 Plays, a collection that includes Boys and his last play For Reasons that Remain Unclear, an autobiographical one-act about a writer who arranges a reunion to confront a priest who molested him.

The playwright’s second work, Remote Asylum, produced in Los Angeles, was about three lost souls: an actress, her tennis pro lover [played by William Shatter, breaking away from Captain Kirk] and a gay writer friend, Michael – introduced in Boys, who escape to a Mexican villa to find themselves and end up dancing on each other’s graves. The reviews were poor. This failure, coming on the heels of Boys’ mega success put Crowley in such a tailspin he escaped to France for two years.

“I tried very hard, couldn’t shake the depression. To do that, I had to change my inner self and get to know the real Mart Crowley.”