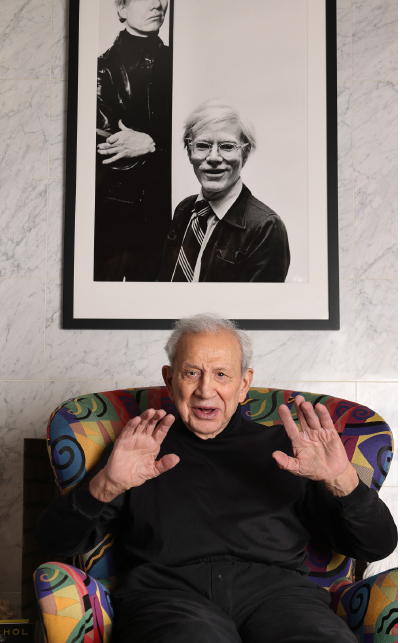

RON GALELLA

A Candid Interview With The Legendary Photographer

By Patricia Canole | Photography Neil Tandy

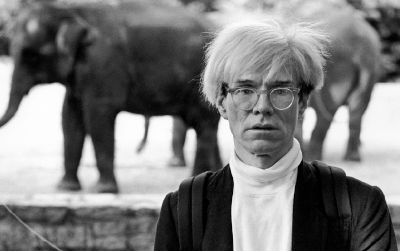

He’s been called one of the most controversial celebrity photographers of all time and dubbed “Paparazzo Extraordinaire” by Newsweek and the “Godfather of U.S. paparazzi culture” by Time.

He has always taken enormous risks to get the perfect shot. As a result, he has endured much publicized court battles with Jacqueline Kennedy-Onassis, a broken jaw courtesy of Marlon Brando, and a severe beating by Richard Burton’s entourage before being jailed in Mexico.

It’s this passion for the fine art of photography, coupled with his personal approach to his craft, which now sees Ron’s body of work exhibited at museums and galleries throughout the world. The Museum of Modern Art New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Helmut Newton Foundation Museum of Photography in Berlin, among others, all maintain collections of his iconic works.

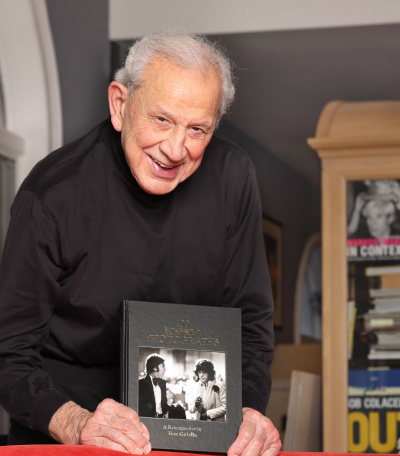

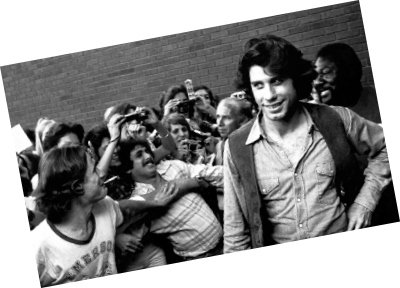

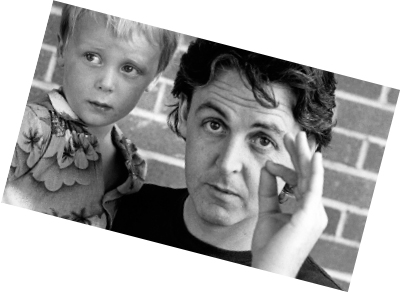

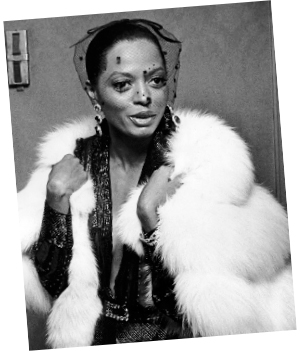

Ron’s insatiable passion has also given us his many highly-acclaimed photo-art books, including Disco Years, honored in 2006 by The New York Times. Soon after it was published, Ron transitioned to film with Smash His Camera, a documentary of his life and career by Oscar-winning director Leon Gast. The film premiered at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival and received the Grand Jury Award for Directing in the U.S. Documentary category. His latest book venture is 100 Iconic Photographs: A Retrospective by Ron Galella and features luminaries the likes of Elvis, Princess Diana, David Bowie, and Paul McCartney, in the spontaneous, off-guard style that only Ron could achieve.

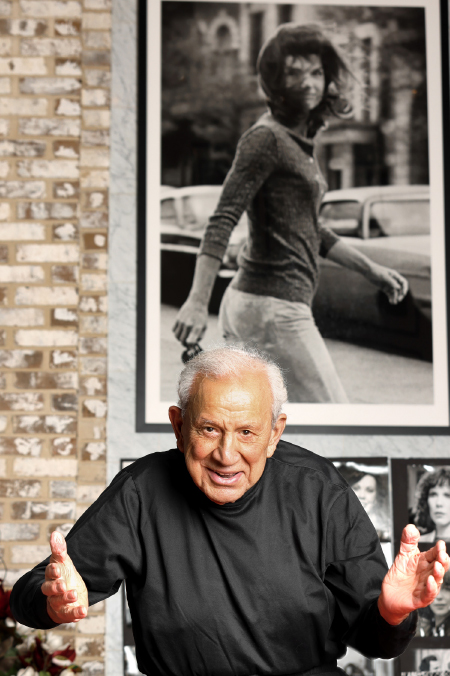

I was recently honored to visit Ron to celebrate the launch of his latest book, the 50th anniversary of perhaps his best-known photograph Windblown Jackie, and his 90th birthday. It felt like memory lane for this magazine editor, who was just starting in the business at a celebrity magazine when she first encountered this expert lensman. I’ll never forget his enthusiasm as he delivered the latest scoops of the celebrity world: Hollywood, New York, and points beyond landed on my desk. I often wondered if there were enough hours in the day for Ron Galella.

Naturally, Ron’s visits to my office were highlighted with stories of hair-raising encounters with celebrities. But, unlike today’s celebrity stalkers, he never went to apartments, always tried to remain unnoticed, never provoked stars—all resulting in the ultimate proof that he’s a different breed. While looking at the iconic works gracing his home, I considered how nothing ever really changes. For many of us, we’ll always be curious about the intimate lives of those in the public eye.

I sat down with Ron, reminiscing about the wild stories behind his most iconic shots, the beatings he took for his art, and what has changed since his golden age as a paparazzi.

Tell us about your early years as a boy in the Williamsbridge section of the Bronx.

I was born the third of five children to my parents both of Italian heritage. Life in our home on Oakley Street was full of surprises for the Galella children.

Though only twelve miles north of Manhattan, the days during the Depression-era Bronx were spent with my brothers and sister inventing games, exploring the countryside, and making mischief. My childhood was filled with watching actors and actresses on the silver screen, doing odd jobs around the neighborhood, and navigating a family life that was loud, antagonistic, and surprisingly permissive—an ideal breeding ground for the paparazzo I would become.

Did your family influence your career as a photographer?

Yes, my mom along with the U.S. Air Force. My mother instilled in me a love of the limelight: Though my brothers and sister were given traditional Italian names, she named me after the Academy Award–winning actor Ronald Colman (she had a thing for dark-haired men with English accents). In addition to raising five rambunctious children, Michelina adored cinema and took me to see many movies.

Tell us how the U.S. Air Force played a role in your career.

Rather than wait to be drafted into the Army, I enlisted in the Air Force. It would prove to be one of the best decisions I ever made. It’s where I learned the basics at the Air Force Photography and Camera Repair School.

The planes—Boeing B-47 reconnaissance and strategic bombers—were all equipped with radar and photographic cameras in the bays. The film from these cameras had to be developed and replaced, requiring two or three sturdy camera technicians like myself. However, there were five of us assigned to the photo lab. Luckily, three volunteered and transferred to the flight operations. I happily remained in the photo lab as a photographer.

During your hey-day in the ‘70s and ‘80s what do you feel were your biggest challenges?

The free speech trial Galella v. Onassis resulted in a restraining order to keep me 50 yards (later changed to 25 feet) from Jackie. I was found guilty of breaking this order four times and faced seven years in prison and a $120,000 fine; later settling for a $10,000 fine and surrendering my rights to photograph Jackie and her children.

Then came the worst day of my life! I was in Cuernavaca, Mexico to photograph the filming of Hammersmith Is Out, in which Peter Ustinov was directing Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. The movie was being shot at the Posada Jacarandas Hotel. The owner, Robert Quiroz, had invited me and authorized me to photograph the Burtons without their knowledge because he was interested in publicizing his hotel. Since Elizabeth and Richard knew me, I wore a Mexican disguise—a mustache and a sombrero hat—and posed as a hotel gardener, pushing a wheelbarrow that held my photo equipment.

Mr. Quiroz let me know that I’d need to hide before 5 pm somewhere around the pool, where

Burton’s party scene was to be filmed. I chose to hide in a cave containing the pool pump, which would conceal the noise from my camera shutter.

Later, while the scene was being filmed, a crew member discovered me in the cave when he went to stop the pump because of the noise. Burton’s film crew took all my exposed and unexposed film from me, along with my hotel key. Then they held me while a crew member went to my hotel and took all fifteen rolls of exposed film I had there—over five hundred pictures from one week of shooting.

After they released me, I went to my hotel and discovered the film missing. I went back to the film set to get my film. Three crew members came and greeted me with a punch to the mouth, breaking one of my teeth, a punch to the eye, and then kicking me causing me to fall to the ground.

The Mexican police who guarded the set finally stopped the violence and took one of the crew members and me to jail. I was finally released, along with the crew member. I went to the hospital with black eyes, a bloody nose, swollen lips, and that missing tooth.

When I returned to New York, I hired Los Angeles lawyers to sue the film company and the Burtons for $1.9 million. I lost this case because Mr. Quiroz did not want to admit that he had invited me to hide in the pool, so he never testified. Burton’s lawyers offered me $1,500 to settle the case, stating that Burton had nothing to do with the incident.

Then, there was the Marlon Brando sucker punch. It happened after a taping of The Dick Cavett Show. Both Cavett and Brando were headed down to Chinatown and I, and a fellow photographer, followed them. Once they reached the restaurant,

Brando mumbled to me if there was anything else I wanted. I asked if I could get some photos without the sunglasses. Then it was a sock in the jaw. The next morning, I read that Brando was hospitalized because five of my teeth were imbedded in his knuckles. I sued him and won a $45,000 settlement.

How have you managed all the criticisms/assaults throughout the decades? Did you ever think that being a paparazzo was invasive or disrespectful?

I’ve been called the godfather of modern paparazzi. Many have disapproved of my work and process, while many others admired my work—like famed fashion designer Michael Kors, who coined the phrase “Galella Glamour.” Andy Warhol called me his favorite photographer. Whether you love me or hate me, my technique yielded intimate, unchoreographed images that could not have been crafted or set up by a PR or marketing team. I stand by my methods because they were the best ways to create authentic photographs by capturing celebrities in their natural environments. My purpose was not to punish my subjects. Far from it, I idolized them!

Although I proudly pioneered the paparazzo approach, I do not approve of the methods employed by the current crop of street photographers, and I even distanced myself from them as far back as 1992.

Did you ever consider a more conventional pathway such as a fashion photographer?

At the beginning of my career, I did not have the funds to open a studio. Living near Manhattan and knowing I could travel anywhere, the world became my studio as a freelance photographer. Most will agree that my greatest fashion photo is my Mona Lisa, Windblown Jackie.

So, tell us how you photographed the iconic Windblown Jackie.

It was a late afternoon in October 1971. I had just finished shooting portfolio shots for a model named Joy Smith, who lived on East 88th Street.

A fool for beauty, I took pictures of Joy because I had nothing else to do—this was pro-bono work and the location was Central Park, directly across from Jackie’s apartment.

As Joy and I left the park, we caught a glimpse as Jackie was leaving her building. Keeping a measurable distance behind Jackie, Joy and I followed her along East 85th until Jackie turned on to Madison.

I decided not to run in front of her because if I did, she’d recognize me. Instead, Joy and I hopped a cab and followed Jackie until we caught up with her between East 89th and 90th Streets. There, I rolled down the window and took two profile shots of Jackie walking. Then, the cabdriver honked his horn without me telling him! This was what Henri Cartier-Bresson, the father of modern photojournalism, called the decisive moment in photography. I had to seize it. Jackie turned and I pressed the shutter release a third time, and that was the shot. Jackie about to walk across the street, no makeup, hair tousled, wearing jeans, glasses in her hand, and a light smile on her lips, her eyes gleaming.

Why do you think the public is captivated with celebrities and their lifestyles?

I believe we would all like to be famous. Most are likely to imagine themselves on the silver screen or on television. The life of a celebrity appears exciting, luxurious and to be famous seems appealing to most.

100 Iconic Photographs: A Retrospective by Ron Galella exemplifies your absolute best celebrity photos. Why did you select John Lennon and Mick Jagger to be the cover?

My top two selling photographs—John Lennon and Mick Jagger (front cover) and Windblown Jackie (back cover)—have one thing in common. The subjects were not aware they were being photographed.

The unguarded moment between two popular, legendary music icons caught in conversation, bathed in soft, diffused light, was captured using a 300mm lens. Mick, wearing a white tuxedo jacket, white scarf, and a carnation in his lapel pocket looking slightly down, and John, in a black tuxedo, looking at him in profile. It was perfect!

For more information visit: rongalella.com

Surely, a look at Ron’s body of work is not only highly regarded for its prized artistic value but also appreciated for its historical significance. As Andy Warhol once said, “My idea of a good picture is one that’s in focus and of a famous person doing something unfamous. It’s being in the right place at the wrong time. That’s why my favorite photographer is Ron Galella.”

All photos © Ron Galella